What if you had to show your ‘working out’?

Somewhere along the way, we’ve started to treat decision-making as a by-product rather than a responsibility.

I see it increasingly in conversations about AI at work. The focus is almost always on efficiency, speed, output, and scale. Rarely do we stop to ask what happens when the decision itself is challenged. Not whether AI was used, because that ship has sailed, but how the conclusion was reached, who applied judgement, and whether anyone can still explain their reasoning without pointing vaguely at a tool.

Imagine being asked, formally or publicly, to justify a decision…a policy choice, a hiring outcome, a safeguarding call, a strategic recommendation, a customer-facing judgement that later unravels.

Imagine that decision was shaped by multiple people, each using AI at different points in the process.

Say, one person summarised information. Another generated options. Someone else refined the language. A final sign-off was given because the output ‘looked right’.

At that moment, ‘showing your working out’ stops sounding like an academic exercise and starts sounding like professional survival.

If you can’t reconstruct how a decision was formed, what assumptions were accepted, what alternatives were rejected, and where human judgement intervened, you don’t really have a decision at all. You have an artefact: a thing that exists, but one that can’t defend itself. In regulated sectors, that’s a compliance issue waiting to happen. In unregulated ones, it’s a reputational risk that just hasn’t found its trigger yet.

This is why I keep coming back to the idea of forensic scrutiny. Not in a dramatic, crime-scene sense, but in the quieter discipline of being able to explain your reasoning under pressure. Forensic thinking is about traceability. It’s about being able to say ‘this is why we did this’, not ‘this is what the tool produced’.

AI doesn’t remove the need for that level of rigour. It makes it more necessary, because the reasoning path is no longer linear or obvious.

The irony is that many organisations are embracing AI precisely because they want to reduce cognitive load, streamline thinking, and move faster. What they’re actually doing, often without realising it, is increasing their exposure. Decisions become harder to audit, harder to defend, and harder to learn from. When something goes wrong, the post-mortem doesn’t reveal insight, it reveals confusion.

And that brings me to the second issue, which feels less technical but may be more corrosive in the long run: passivity.

I’m seeing a worrying trend where people aren’t using AI to underpin creativity or deepen thinking, but to replace it. Prompts are treated as substitutes for effort. Outputs are handed in with minimal interrogation. The bar quietly lowers, not because expectations have changed, but because it’s easy to mistake fluency for competence.

The problem isn’t that people are using AI. It’s how little thinking they’re doing around it.

If you can’t explain why you accepted one suggestion and discarded another, you haven’t exercised judgement. If you can’t articulate what you learned through the process, you haven’t developed. Over time, this doesn’t just make individuals less employable. It makes them brittle. They struggle when the context shifts, when the tool fails, or when they’re asked to justify their position rather than present a polished output.

From an employer’s perspective, this should be setting off alarm bells. A passive relationship with AI creates a workforce that looks productive on the surface but lacks depth beneath it. That’s a risk, not an advantage. When pressure hits, when scrutiny arrives, when decisions need defending rather than delivering, the cracks will show quickly.

What worries me most is that this passivity isn’t just an individual failing. It’s being normalised. We’re rewarding speed over sense-making, completion over comprehension, outputs over ownership. In doing so, we’re training people out of curiosity and into deference. Not deference to managers or systems they understand, but to opaque processes they can’t interrogate.

Which leads neatly, if uncomfortably, to the bigger picture.

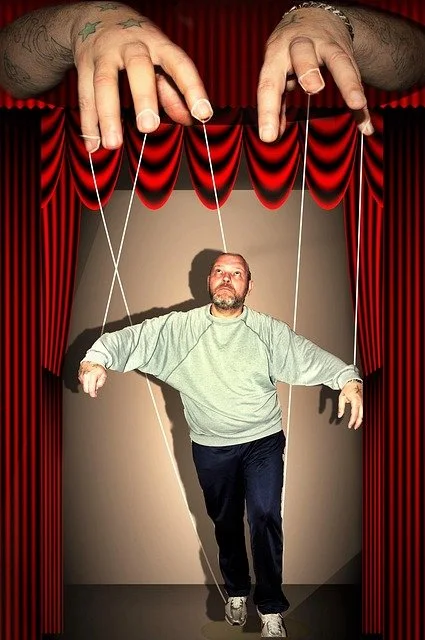

When people stop thinking deeply about how decisions are made, someone else starts thinking for them. Not in a dramatic, dystopian way, but gradually—through defaults, incentives, and convenience. The same handful of companies shape the tools, the data, the frameworks, and (increasingly) the language we use to describe problems. If you rely on those systems without scrutiny, you also inherit their assumptions, their priorities, and their blind spots.

We already live in a world where media influence is concentrated, political narratives are shaped upstream, and public discourse is mediated by platforms with commercial incentives.

AI accelerates this by embedding those influences directly into how work is done, how ideas are generated, and how options are framed. When millions of people use the same systems to think with, diversity of thought narrows even if the outputs appear varied.

The real danger isn’t that AI will control us outright. It’s that we’ll quietly outsource parts of our thinking without noticing where our agency ends. We’ll accept suggestions because they’re plausible, persuasive, or efficient, without asking whose outcomes they serve. Over time, the line between our judgement and someone else’s objectives will become harder to see.

This is why I believe forensic decision-making is no longer a niche concern for lawyers, auditors, or investigators. It’s a core skill for anyone who wants to remain professionally credible in an AI-saturated world. Being able to slow down, interrogate inputs, justify conclusions, and own the reasoning behind them isn’t a luxury. It’s a form of resistance against intellectual apathy.

None of this means rejecting AI…quite the opposite. It requires engaging with it properly. Treating it as a collaborator to be questioned, not as an authority to be deferred to. Building cultures where ‘how did you get there?’ matters as much as ‘what did you produce?’. Valuing learning and judgement over polished outputs that collapse under scrutiny.

If there’s one question I keep returning to, it’s this: if you were asked tomorrow to defend your decisions in detail, could you do it without pointing to a tool? Could you show where your thinking began, where it was challenged, and where it ended?

Because if the answer is no, it might be worth asking who, or what, is really deciding on your behalf.